After he broke his back in a 480-foot fall, the BASE jumper’s life changed. Now he’s rediscovering how to catch air by throwing backflips in a sitski.

Professional BASE jumper Miles Daisher needed a new roof on his house in Twin Falls, Idaho. So Daisher, who regularly teaches BASE-jumping courses, posted a trade offer online: help install his roofing and he’d teach a qualified person how to BASE jump. Which is how, in 2013, a 23-year-old skydiver from Florida named Jay Rawe and two friends ended up piling into a three-seater pickup truck and driving across the country in 36 hours from Florida to Idaho to learn how to BASE jump.

“I recall Jay as being very eager, with big eyes and a thirst for learning and going big,” says Daisher. The three guys worked for a couple of weeks on Daisher’s house, and in exchange, he coached them at Twin Falls’ Perrine Bridge, one of the few structures you can legally BASE jump from in the United States. “I was hooked right away,” says Rawe.

After that, Rawe moved to Draper, Utah, where he worked as a bartender at a steak restaurant and continued to BASE jump whenever he could. A year later, on March 24, 2014, Rawe, then 25, and his friend Austin Carey, then 23, showed up at the Perrine Bridge. After two flawless jumps, they decided to try something different: a tandem jump, a move that’s not uncommon in BASE jumping.

Carey stood on the edge of the bridge, and Rawe climbed onto his friend’s shoulders. But then, as they leaned forward, Carey’s parachute wrapped around Rawe’s leg, tangling their chutes. Both men fell 480 feet, hitting the ground below. In a video of the accident captured by their friends standing on the bridge, all you can hear are loud gasps and the words “Oh my God.”

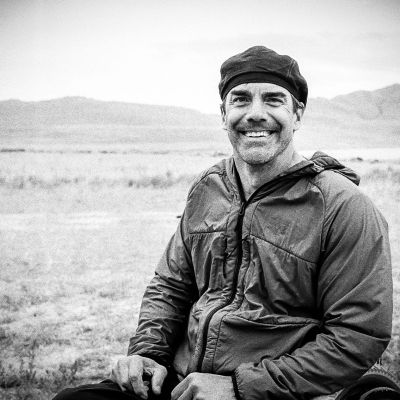

When Rawe was a kid in Bradenton, Florida, anytime he went missing, his teachers would say, “Look up.” He was usually hanging from the monkey bars. “He was always on top of something,” says Jay’s mom, Teresa. “When he was three, he climbed on top of the refrigerator.”

She enrolled him in gymnastics so he’d learn to fall gracefully. Later he wrestled, skateboarded, and had dreams of becoming a Hollywood stuntman. “I’ve always had an inclination to do flips and jump off things,” says Rawe, who’s lean and clean-cut, with a square jaw, friendly blue-gray eyes, and neatly cropped brown hair.

sports

(Photo: Courtesy Teresa Rawe)

At 21, he learned to skydive at a popular drop zone in Zephyrhills, Florida, an hour and a half from where he grew up. “I started researching BASE jumping and found out that you had to be a skydiver first,” Rawe says. “I always wanted to fly, and the safest way to do that would be with a parachute. But you have to have 200 skydives before anyone will even teach you to BASE.”

His mom admits she was constantly nervous about her son’s level of risk-taking, especially once he learned how to BASE jump. “He wouldn’t tell me until after he landed that he was climbing on top of a tower,” says Teresa. “He’d take pictures of sunrises and text me afterward to say, ‘Look what I saw today.’ I voiced my opinion that it was unsafe, but there’s only so much you can do.”

After hundreds of successful skydives and then a year of BASE jumping with instruction from Daisher, Rawe made that one major mistake. Usually, that’s all it takes. That dual jump off the Perrine Bridge in 2014 could have killed both him and Carey, but instead it broke both of the young men’s backs.

It was a miracle he wasn’t paralyzed. Rawe suffered a burst fracture of his L1 vertebra—basically a severe compression of his spinal cord—and underwent surgery that night. He spent a week in the hospital in Idaho, then months in a rehabilitation center in Florida. He had severe nerve damage, and doctors weren’t sure if he’d ever retain full movement. “I tried to stay positive. I never once had bad thoughts,” Rawe says. “Doctors told me, ‘You might never walk again. You have to accept this as your new life.’ Inside, I was like, ‘No, I’m going to be jumping again.’ I was very confident in my ability.” After months in rehab, Rawe was back on his feet, walking with a cane.

Seven months after the accident, Rawe actually did do another BASE jump, off the New River Gorge Bridge in West Virginia. He did a few more jumps and skydives after that, but things had changed. “There was definitely more fear there,” Rawe says. “I think time made the fear bigger.”

Two years after his accident, Rawe was depressed. Despite his attempts to return to BASE jumping, the nerve damage in his left leg and his spinal injury were just too much. He couldn’t really do the things he was used to doing—skydiving, snowboarding, and riding his bike were challenging, to say the least. He was back home living with his mom in Florida, and his life felt stalled. “He wasn’t able to do anything exhilarating and challenging, and his quality of life wasn’t the same,” says Teresa.

So when Rawe and his girlfriend set out on a cross-country drive in the winter of 2016, Teresa suggested they stop in Breckenridge, Colorado, and visit the town’s adaptive-sports facility, the Breckenridge Outdoor Education Center. There, Rawe learned to use a sitski, a device that enables those with debilitating injuries to sit in a bucket-like seat and slide down snow on a single ski, using outriggers on your arms for balance. Rawe had learned to snowboard as a kid on occasional family trips to the mountains, but the sitski was an entirely new beast. “I was back on the bunny hill,” he recalls.

Rawe took more lessons that winter in Utah at Wasatch Adaptive Sports in Snowbird and the National Ability Center in Park City, spending a total of eight days that season in a sitski. Not bad for a guy who lived in Florida. He eventually applied for a grant from the High Fives Foundation, an organization based in Truckee, California, that helps people with life-altering injuries, which covered the cost of his physical therapy. He saved money for a year to buy his own sitski, which cost about $5,000.

In November 2017, Rawe moved to Lake Tahoe; he wanted a change of pace and he had some friends there. That winter he quickly went from skiing groomers at Squaw Valley to venturing into the terrain park on his sitski. “I rode over the little boxes and rails and slowly progressed to the jumps,” he says. He talked to veteran adaptive skier Bill Bowness, who works as an instructor at Achieve Tahoe, the area’s adaptive-sports program. Bowness offered him tips on landing and balancing his sitski. “I was going over little side jumps and wrecking,” Rawe says. “Bill told me, ‘Don’t lean forward. Whatever direction you’re leaning is the way you’re going to go.’”

At the end of last winter, Rawe met another sitskier in the park at Squaw Valley, a 26-year-old named Trevor Kennison, who broke his back snowboarding in the backcountry of Vail, Colorado, in 2014. The two pushed each other to learn new things. “It’s rare to see another sitskier in the park,” Kennison says. “There’s not many people who do what Jay and I are trying to do, and his stoke level was high.”

By sitski standards, Rawe’s moves were groundbreaking. He progressed gradually, from regular airs to shifties, then 180s, then a quarterpipe trick he calls a pole-plant alley-oop, a 180 where he spins uphill. He was hitting cliffs on big-mountain lines, and in spring 2018, he stuck his first backflip off a jump in the park. In the process, he skied about 80 days and broke 11 skis (not the pricey bucket-seat contraption but its single ski, which he’d replace with hand-me-downs from friends).

Canadian Josh Dueck became the first sitskier to throw a backflip, in 2012. “A lot of people are like, ‘I want to do that.’ Then they get out there and realize how hard it is,” says Dueck. “It’s exhausting.” For years there’s been ski racing for adaptive skiers but little in the way of freeride programs. Dueck teaches a freeride adaptive camp through Canada’s Live It Love It Foundation, but beyond that, there’s not much in the way of organized big-mountain or park-and-pipe skiing for adaptive riders. The X Games introduced an adaptive ski-cross event, called Mono Skier X, in 2007, but it hasn’t taken place in several years due to a lack of potenital participants.

sports

(Photo: Courtesy Jay Rawe)

But now there seems to be a growing demand for competitions among rising adaptive freeriders like Rawe and others, who operate on their own but could benefit from an organized program. There’s Kennison, who has considered entering Freeride World Tour qualifier events. Then there’s a skier named Rob Enigl, who’s doing first sitski descents around Montana, and a Marine sergeant named Trey Humphrey, who lost his right leg after stepping on an improvised explosive device in Afghanistan and is now doing sitski backflips into foam pits.

Rawe would like to see more of this progression among adaptive athletes. He and Achieve Tahoe instructor Keagan Buffington have an idea for a first-of-its-kind adaptive freeride festival, where skiers with varying disabilities could get together and shred big-mountain terrain or throw tricks in the park or pipe. Maybe it’d be a competition, maybe a clinic, or just a gathering of new friends. “We thought, Let’s get a bunch of the best sitskiers who want to ride steep terrain together and see where this goes,” says Rawe.

Achieve Tahoe’s executive director, Haakon Lang-Ree, says the organization is open to the idea of hosting an event like this, but a date hasn’t been nailed down (though it could happen as early as next winter). “We’re not going to have 12 people throwing backflips. These are great ideas and dreams, but this type of riding isn’t for everyone,” says Lang-Ree. “But the more models you have, the more people will try new things and look at more terrain. Once you have mastery of the mono-ski, you’re about as limitless as anyone standing up on two skis.”

As for Rawe, he’s still working on his own moves. “The hardest part is working up the nerve to hit a jump for the first time,” he says. “It’s this big unknown, but then you do it and you’re fine, and you know: I can do this. All outcomes are possible.”